|

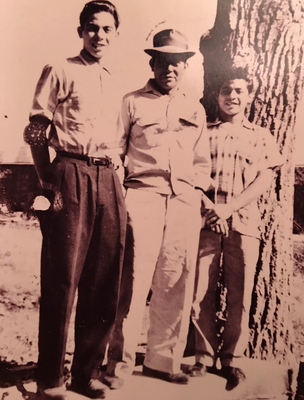

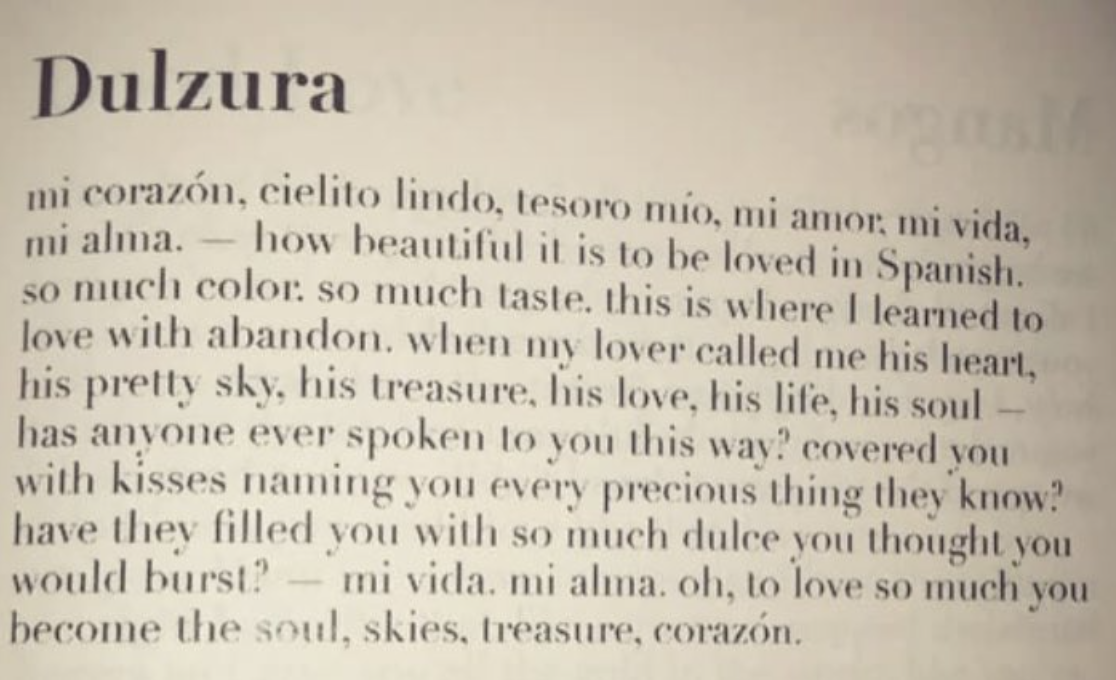

This piece was originally published on my Medium site in October 2017. It has been edited and updated to reflect today. I don’t speak Spanish. For many of my online community, whom I don’t know irl (in real life), it comes as a shock that I don’t speak Spanish fluently, and it’s pretty embarrassing for me. I can read it enough to get by, and I can understand Tex-Mex conversations, but forming a sentence and connecting through colloquialism is more difficult. While in Puerto Rico, I struggled even communicating basic things that left me frustrated and sad. It is a common occurrence for many people my age, of similar background, who identify as people of color but don’t speak the language of our elders or ancestors. In my case, this erasure was a method of preservation and survival. As recent ago as the 1950s, Mexican-American children in South Texas were not only segregated from White schools, but in 1954 when the US Supreme Court outlawed school segregation, children were then punished for speaking Spanish, for being Mexican-American, and having a “Spanish sounding” last name. My eighth grade English teacher Mrs. Garza once shared with us that the first time she felt utter humiliation was as a very young girl who had to use the bathroom while in school. She did not know English or the translation of, “¿Puedo ir al baño?” Her teacher would not allow her to use the bathroom until she asked in English without help. As then-Mrs. Garza did not know how to speak English, she soiled herself in front of her classmates, and cried all the way home in deep shame and embarrassment. My grandparents have shared similar stories of being punished for speaking Spanish in school, and discovered speaking Spanish was more harmful to survive and make a living in American society. Mi abuelo shared he didn’t care if his teachers told him not to speak Spanish, he spoke and got in trouble anyway. He later didn’t learn English until he joined the military. My grandma says her accent caused people to think she is unintelligent. In the documentary “Stolen Education,” stories of elders who were children during this violent time and victims of educational stagnation merely for being themselves, are re-told with more heartbreaking personal accounts. Across the United States, many American ethnic minorities have similar experiences in which their cultural language and method of sharing was stripped from them in order to assimilate. This is an ever ongoing occurrence and discussion. The difference being, for many South Tejanxs “the border crossed us” and our forced assimilation is even more gruesome. My grandparents decided not to teach Spanish to their children or grandchildren for this reason. While growing up in the 1990s, it was embarrassing for my classmates to speak Spanish or have an accent. It was one of the more obvious “othering” markers, even in a school that was already full of “others,” with 80% Mexican-American or Latinx students. When I went to college at a predominantly White, conservative school and took Spanish classes, I felt completely defeated. My accent was naturally better than anyone else’s in my class, I was constantly asked to be study partners with my non-Latinx classmates, but I was worse off than all of them. I struggled referencing “proper” Spanish with the Tex-Mex Spanish I had grown up with and never quite accepted as my own tongue. Now, privileged English-speaking families in the US often pay upwards of thousands of dollars to send their children to schools that teach Spanish. Sometimes they raise their children with nannies who teach it to them as we've seen with Beto O'Rourke. We spend hundreds on apps or programs that claim to teach us other languages. Speaking Spanish in many professions is “rewarded” with better pay or opportunities. Language is powerful because it shapes our world. It shapes the way we think and actualize our lives: the way we communicate with each other in intimate settings and in broad demonstrations. Language is how we feel. I didn’t begin to recognize this power fully until I read Sandra Cisneros's work. She is a fellow San Antonian and one of my personal heroines. La Sandra writes in English and Spanish, intermixing the languages in a way that made sense to me, a Brown girl in an American world. I wasn’t inspired to write this until I read Yesika Salgado’s poem “Dulzura,” in which she describes how much more full and “beautiful it is to be loved in Spanish.” Different languages create completely different perspectives by way of putting words to our feelings and making them shareable in order to connect. I often feel I've lost a lot of this context and other perspective to feel and experience the world. In one of my favorite movies “Selena” we see her struggle with speaking Spanish versus singing it. Selena taught herself Spanish mostly on her own when she was a young woman, but spoke openly on her experiences in growing up as a Tejana — more American than Mexican, exactly like me.

All of this is to say that my experience and context isn’t an unusual one. I am now teaching myself Spanish as a means to connect with communities better and to understand myself more fully. As we see students protesting their teachers for demanding Spanish-speaking students speak “American,” we must be cognizant of our historical and cultural pasts to fully understand ourselves. Fully understanding ourselves includes recognizing our place in modern society and its oppressive pitfalls so we can fully organize for autonomy and political stakes. Spanish is the language of my ancestors’ and my colonizers, and in that knowledge I allow for more self-reflection, reclamation, and empowerment to the next steps. To recognize language evolves, and that societies reflect our historical happenings is paramount if we are to fully stand in our power. Communicating in various languages is a profound skill, one we should stand proudly in and reclaim.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About:Keep up with my musings about political chismé, life, my relationship, food, San Anto history, my dog, and everything in between. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed